【注:这是拿黄老师CH3245(海外华人)课时做的作业,于18年2月完成。此贴仅做参考。】

一、武吉布朗坟场简介

早期来到新加坡的华人为了生活与交流之便,会按照自己方言、地域、家乡来分开居住。这种区分也反应在早期华人的埋葬分部中。例如早期处于中峇鲁地带的新坟山,是新加坡首座福建人的公墓而乌节路地带的泰山亭则是新加坡最早的潮籍华人坟山之一[1]。武吉布朗坟场是先经林文庆倡议,后由陈谦福和薛中华先生附议,最终由英殖民政府于1922年1月1日开建[2]。有别于那些早期的坟墓,这座坟场不以方言或地域区分人,是整体华人的共同坟场坟场。几十年下来,坟场历经英殖民、二战、日治期、新加坡自治和独立,直到1973年才被关闭[3] 。

自2011年起,出于对土地的需求,新加坡政府有关部门决定穿过武吉布朗坟山修路、搭建居宅和地铁站[4]。原共共计约十万座坟墓,七年来已近5000座坟墓因工程遭受波及。

(图1-2:左图取自陆路交通管理局网站,右图取自Google 地图)

将坟场的卫星视图同陆路交通管理局(Land Transport Authority)所提供的修路蓝图做对比可见,新修的路分别从亚当高架道路(Adam Flyover)和麦里芝高架桥(MacRitchie Viaduct)两侧直切坟场。看进度,应该不久之后就能连成一条完整的线。

当时有很多群众自发地走出来呼吁要保留这片珍贵的历史活文物,可惜这未能彻底改变政府的决定。不过这些响应还是让很多大众认识到这座沉默的坟山,并且趁坟山完全消失之前,陆续自发到此地学习观察。值得一提的是,由于坟场早在1973年就被关闭,所以大众(特别是年轻的一代)对坟场不太了解,反而是这政府的政策引起更多讨论与观众。

二、田野考察

在很多人眼中,坟场应该是一个不太吉利的地方,多数人除了去上坟以外,应该很少有人特地去那里。所以父母这次一听我上课做田野调查竟然调查到坟场里去了,都是一脸不赞同地训斥我:“你看看你,现在感冒那么严重,又是女孩,身上阳气弱,还要去坟墓?!”虽然之前多次在报纸上看到关于武吉布朗坟山拆迁的新闻,但是我还从来没有亲自来过一个墓地。这次学校带我们去,我顶着“为了了解坟场宝贵的历史文化遗物我义不容辞”的名义说服父母,事实上主要是怀着好奇和猎奇心理跟随老师同学一起来到武吉布朗坟山。

(图3:武吉布朗坟场入口“山丘1”的景色,笔者摄。)

站在山坡下,立刻映入眼帘的就是满山郁郁葱葱的树木和一排排的坟墓。这里是死者的葬身地,又是草木的栖息地。一生一死,本应形成极强烈的反差,却又好似沉浸在彼此的安宁祥和中。很难想象,不久以后,这里很可能是那些坟墓和草木的终极墓穴。

- 坟墓的结构

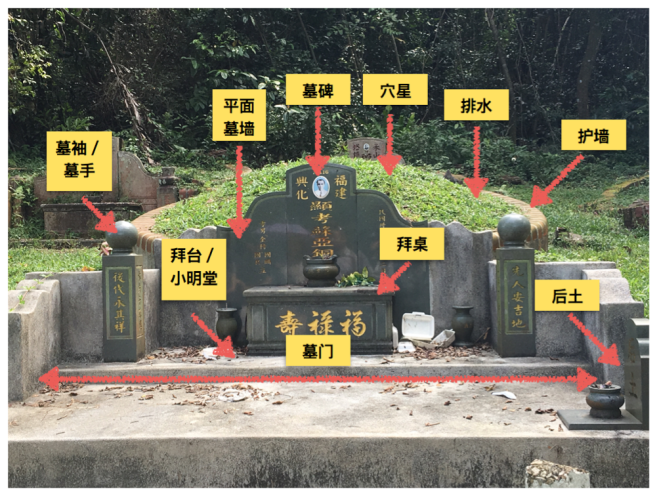

由于坟场是公坟,位置有限,所以每做坟墓不可能过于复杂。据观察,绝多数坟墓是属于“环墓”的格局,其又分“单环”和“双环”。这种坟墓造型在中国闽广两地是最为常见的[5]。由于早期来新的华人多数都从这两处沿海地区南下,因此也带来当地的葬墓风俗。我借用一位逝世者的坟墓制作成一张坟墓构造展示图:

(图4:坟墓的结构展示[6]。苏亚铜先生之墓,1942年4月18日[民国卅一年四月初二]逝。笔者摄。)

葬在环幕的死者通常会被葬在墓碑后,与前来祭拜的后人相互隔开,避免后人踏在死者的遗骸之上。图4显示的是一座单环墓,就是将遗体埋葬在墓碑后,以一环护墙环绕坟墓,在下雨时可以引导水往坟墓两边走,不会渗透到坟土地下[7]。双环墓则是在单环墓的基础上再添加一环,一为风水之用,二为排水之用[8]。早期华人来到新加坡多数只是为了赚钱养家,心中的“祖国”还是中国。但是由于种种原因葬在“异乡”,这时在墓碑上刻下自己的祖籍地便是极其重要的,可能象征着对自己故土的怀念和文化的延续。多数坟墓侧面都会立“后土”或“福神”的碑牌。

(图5-6:武吉布朗坟山的“后土”、“福神”碑牌。笔者摄。)

“后土”早期在道教是指“与玉帝同阶位” 的身份,后来演变成一种一“大地为人类之母的信仰”[9],葬在墓边则有守护墓地、保护死者的作用。

此外,人们也会在墓袖上立起镇墓兽,以驱邪守墓,保佑亡者灵魂的安宁。当然,镇墓兽的式样和规模也会根据死者与后人的经济实力或个人选择而变化。

(图7-9:几种不同的镇墓兽。笔者摄。)

中图和右图的镇墓兽则是狮子形状的,雕刻精致细腻,栩栩如生,而右图中的镇墓兽的更是被涂上金漆。左图中的墓袖上刻的就是圆形和尖形的,可以被视为一个镇墓兽的浓缩象征符号。

以上提到的是坟墓的大致结构,但坟墓构造在地区之间也有差异。虽然福建和广东相隔不远,但是两处的坟墓也有一些区别。坟墓后面的护墙出,但是通常这种护墙在闽南式的坟墓比较常见:

(图10-11:左图为闽式坟墓,右图为潮式坟墓。笔者摄。)

如图所示,闽式坟墓有一环护墙包围死者所卧的范围,除了防雨,也可以清楚地划分埋葬死者的范围。潮式的坟墓则是以小环围绕墓碑,埋葬死者的部分则同周边的草地混为一体。

除此之外,潮闽两地的墓碑也有些区别:

(图12-13:左图为闽式墓碑;阮汤丙娘女士之墓,民国十五年丙寅三月十四日[1926年3月24日]逝。右图为潮式墓碑;沈受通先生之墓,丙寅九月廿四日[1926年9月24日]逝。笔者摄。)

闽式墓碑一般会将死者的祖籍写在墓碑的最顶端,如左图中的阮丙娘女士,就是从中国南安来的。潮式墓碑则一般不写死者的祖籍地,要写也是用细小的字体将祖籍地写在旁边。右图沈公的祖籍地就是刻在墓碑的左下角,记录他是从潮安华美村来的。此外,潮安墓碑有一个特点,就是墓碑上的字是死者生前亲自准备的,刻了字后会上红漆,只有等死者被葬入之后,才会被后人涂上绿漆。

- 西化和本土化

来到新加坡的华人一方面会坚守自己的文化与习俗,但另一方面也会受西方文化或新加坡本土文化的影响,从而调整自己原本的文化。坟山上的坟墓种种特征(如墓碑形状、碑字的语言、守墓雕塑、对联等)都显示出西化和本土化的影响。由于新加坡处于东西文化的交界地带,又曾是英国殖民地,所以英语在本地的影响十分深渊。因此,有些墓刻的用语会用中英文双语来记录死者的前生:

(图14:其中一座使用中英文双语言刻字的墓碑。郑治娘之墓,1933年10月28日[民国廿二年廿八日]逝。)

墓碑上用中文刻的是:“福建传门郑氏治娘墓”,而拜桌下方用英文刻写的则是:“In loving memory /of the late/ Madam Tay Tam Neo/ Died on 11 Feb. 1934”。这种双语墓刻的现象在中国应该较为少见,反而在新马区带更常见。

另外,有个别坟墓也受到西方文化与信仰的影响,调整墓碑的外形与坟墓的整体结构。

(图15:西化坟墓之例。左为王平福先生之墓,1959年11月19日[民国己亥年十一月十九日]逝。右为其妻王(林)育環之墓,1968年4月11日[民国戊申年四月十一日]逝。笔者摄。)

这座夫妻坟墓不仅使用双语刻字于墓碑,而且墓碑形状也与西方墓碑的形状相仿。此外,坟墓格局也与其他中式坟墓有差异。坟山其他坟墓都是将死者葬在平地上的层面,使得坟墓突起。然而这座坟墓却将死者埋在地底下,没有突起的“穴星”。一般来说,基督徒或天主教徒逝世后应埋葬在各自教会的坟场,但是武吉布朗坟场内多次出现信仰西方宗教的华人独特的坟墓构造。这可能展现出死者在宗族和信仰之间的冲突与妥协。

有些坟墓甚至还有人形锡克人的雕塑作为守护人:

(图16-17:左图为王三龙先生与其妻王(杨)贤娘女士之墓的锡克人雕塑之一。右图为周玉龙先生与其妻陈淑慎女士之墓的彩色锡克人雕塑。笔者摄。)

左图的那座锡克人雕塑处于全场最大、最高的王三龙先生与妻子的坟墓,于1917年从中国制作并运送到新加坡[10]。锡克人(Sikh)以高达威猛的形象和勇猛的性格显著。当时新加坡英殖民政府也请很多锡克人做警察。因此,近代坟墓也有融入锡克人雕塑的习惯。从上图可见,这些锡克人雕塑身穿正式制服,手持枪支,摆出一副巡逻的样子。这种雕塑的加入也是受到新加坡生活文化影响、是一种墓地本土化的证明。

此外,墓袖上刻的对联也能透露出死者对家乡的归属感问题:

(图18-19:左图为陈延谦先生与其妻葉珠慧之墓,1943年2月23日逝。右图为陈先生自提的对联。笔者摄。)

右图对联为陈延谦先生生(1881-1943)亲笔:“盖棺便是吾庐,埋骨何须故里”。有别于以往华人所讲究的落叶归根的习俗,陈先生表示自己的家乡不在一个特定、原有的土地,而是自己安居的地方就是自己的家的心态。

陈延谦先生于福建同安生,1899年来新,成功建设橡胶厂裕源号,很快就积累了一定的财富[11]。除了积极投身于本地中文教育以外[12],陈先生也热爱艺术[13],留下的遗赠于1956建立来陈延谯基金,其中包括国大陈延谦艺术奖(NUS Tan Ean Kiam Arts Award)[14]。写到这里,我恍然发现自己所在的___________也是这份奖项的受益团体,去年十月还参加了这个奖项的颁奖典礼(去支持朋友)。

(图20:此处应有图,但我出于隐私问题把图拿掉了)

回想起当时参加这场典礼时,只是奖“TEK”(陈先生名字的缩写)视为无关紧要的符号,对其毫无感觉,更不会想要去主动了解。没想到四个月后,竟然能够在这种情况下与陈先生重逢,而这些陌生的符号现在我眼中也变得鲜活起来。

三、结尾

发展与建设对于一个国家,尤其是对于土地空间极其有限的新加坡来说,是极其重要的。客观来看,与其留下一片看似对社会没有积极贡献的土地,似乎将其分配去修建一些比较实际的建筑会更有用。但当我们真正走入这片被封尘已久的土地,扫开灰尘之后,就会惊叹于其所蕴含历史、文化艺术记载之丰富。若任意拆迁而不做任何保留,那会无意中将许多珍贵的素材销毁,日后会后悔莫及的。我觉得武吉布朗坟场的消失是无可避免的,现在只是时间长短的问题罢了。而我们所能做的,就是与时间赛跑,趁它还没有完全消失之前,多去看看它。

Endnote:

[1] 林佳憓 . “他们让位给你住.” 联合早报网, 联合早报, 6 Apr. 2017, <www.zaobao.com.sg/znews/singapore/story20170406-745488.>

[2] Leow, Claire, and Catherine Lim, editors. World War II @ Bukit Brown. Singapore Heritage Society, 2015. Print. pp. 6-7.

[3] Saparudin, Kartini. “Bukit Brown Municipal Cemetery.” Singapore Infopedia, 13 July 2009, <eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1358_2009-07-13.html>.

[4] Ibid.

[5] 王琛发《华人义山与墓葬文化》,(吉隆坡:艺品多媒体传播中心出版,2001),页123。

[6] 坟墓构造图参考:王琛发《华人义山与墓葬文化》,页121-128。

[7] 同上,页123。

[8] 同上,页126。

[9] 同上,页187。

[10] Aggarwal, Vandana. “The Sikh Guards of Bukit Brown.” The New Paper, 6 Aug. 2017, <www.tnp.sg/news/singapore/sikh-guards-bukit-brown>.

[11] 1911 Revolution: Singapore Pioneers in Bukit Brown. Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, 2013.pp. 32-37.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Leow, Claire, and Catherine Lim, editors. World War II @ Bukit Brown. Singapore Heritage Society, 2015. Pp. 187.

[14] 同(11)。

参考资料:

中文书籍:

王琛发《华人义山与墓葬文化》,(吉隆坡:艺品多媒体传播中心出版,2001)。

英文书籍:

1911 Revolution: Singapore Pioneers in Bukit Brown. Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, 2013.

Leow, Claire, and Catherine Lim, editors. World War II @ Bukit Brown. Singapore Heritage Society, 2015.

网络资料:

Aggarwal, Vandana. “The Sikh Guards of Bukit Brown.” The New Paper, 6 Aug. 2017, <www.tnp.sg/news/singapore/sikh-guards-bukit-brown>.

“Final Notice of Exhumation of Graves (Part of) at Bukit Brown and Seh Ong Cemeteries.” Land Transport Authority of Singapore, 22 Sept. 2014.

<www.lta.gov.sg/content/ltaweb/en/roads-and-motoring/projects/Exhumation.html>.

林佳憓 . “他们让位给你住.” 联合早报网, 联合早报, 6 Apr. 2017, <www.zaobao.com.sg/znews/singapore/story20170406-745488>.

Saparudin, Kartini. “Bukit Brown Municipal Cemetery.” Singapore Infopedia, 13 July 2009, <eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1358_2009-07-13.html>.